HMS: Knowing Chicago’s Ropes

In 1969, after qualifying to become an elementary school principal, I was given my assignment – and it proved to be in a high-crime neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago.

I didn’t know whether I should take it or not. I was apprehensive because it was the year after half of Chicago was burned down in the riots following Martin Luther King’s assassination. There was a lot of anger in the air, and a lot of anti-white anger. And here I would be replacing a black principal in a predominantly black school, at a time when only 8 out of 400 principals in the Chicago school system were African-American.

Was this a wise thing to do? I wasn’t sure, and so I decided to go to New York and get the Rebbe’s advice.

What happened in that audience with the Rebbe only intensified the awe and admiration I already had for him. It was a very special audience.

I asked the Rebbe a very serious question pertaining to my future: “Shall I accept this assignment in the heart of an African-American neighborhood or not?” But instead of answering me, the Rebbe responded with a question of his own: “Will Mayor Daley run for reelection?”

I didn’t understand what he meant – I didn’t see the connection to my question, but when he asked me this question a second time, I answered, “Yes, he will probably be mayor for the rest of his life.” I was speaking about Mayor Richard J. Daley, the father of the recent mayor of Chicago, who did in fact die in office after serving as mayor of the city for 21 years.Then the Rebbe came back to my original question and gave me this advice: “Ask the second-in-command.”

I didn’t understand what he meant, but that was the end of the subject. I went outside and my head was spinning. I had come all the way from Chicago for advice, and this was the advice the Rebbe gave me!

I went back home as puzzled as I had come. And so I decided to go up to central headquarters and talk the issue over with an old colleague, a non-Jew by the name of Guy Brunetti, who was the Director of Employee Relations. I said, “Guy, I don’t know what I should do. What do you think?”

He told me, “Well, you will be replacing one of the few black principals in the whole system, but he is not being let go – he is being promoted. So it seems to me that it’s okay for you to take that job. You won’t be perceived as a white man having pushed out a black principal.”

No sooner had he finished the sentence, when someone poked his head into the office and said, “Congratulations, Guy! The Board of Education in

executive session downstairs has just voted to make you Assistant to the General Superintendent.”

And, as I heard these words being spoken, a bright light went on in my head – at that moment I understood the Rebbe. Here I was asking advice of the second in command. And everything was absolutely clear.

The key factor was that Mayor Daley controlled everything. He was a law-and-order mayor, and he appointed the Board of Education. Of course, the superintendent and the assistant to the superintendent were all part and parcel of the same power structure. And then i realized that the Rebbe knew a lot more about Chicago than most Chicagoans. It all came together.

So I did take that job, and I was there for 19 years until I retired. During my tenure, in the late 1970s, an opportunity came up to transfer to a different school, and when I wrote the Rebbe asking his advice, again I received a cryptic answer.

I think it’s very interesting that the Rebbe was so unpredictable in terms of his responses. In many, many respects, he was so far ahead of everyone that sometimes his answers were not quite understandable.

In this instance, a job opening had occurred in one of the most advanced schools in Chicago, in the West Rogers Park neighborhood. By this time I had spent a number of years working in the highest crime district in the city, and I felt I would love to transfer to a school with high academic standards that was also walking distance from my home.

When I asked the Rebbe’s advice regarding this issue, I wrote a letter listing the pros and cons. And, of course, the pros – as I described them – far outweighed the cons, in terms of travel time, in terms of personal stress and so on.

In his response the Rebbe told me to stay put, not to transfer, and he gave a most interesting reason why.

Now I knew that that the Rebbe cared very much about deprived children. At one point he had sent me a three-page educational mandate – which wasn’t just for me but for all educators – where he stressed that teachers had to be very, very sensitive to the needs of their students. One of the things that was so devastating to students in poor neighborhoods or students from broken families was lack of self-esteem. And many members of my faculty would not be sensitive to this. They would speak down to these children, and teach at a level below the students’ abilities. But if a student is not challenged, then a student is not going to succeed. So one of the key themes that the Rebbe had tried to get across to educators was that every child has potential and many times it’s unrealized because teachers, instead of being helpers, are actually obstacles and not facilitators.

But, in this instance, he did not cite this as his reason. He gave another reason altogether. He said, “Last in, first out.” And he also added in Hebrew, “V’Od Taamim – There are other reasons as well.” I asked my mentor, Rabbi J.J. Hecht, what that could possibly mean, but he couldn’t explain. He said, “Don’t ask, just do.”

So what happened? I withdrew my application for that job, and a very good friend of mine, who was also Jewish and who also lived in West Rogers Park, got it. But before long, he was replaced by an African-American principal, and he was transferred even farther away from home than I was. This happened because the federal government had enacted a desegregation mandate for administrators, and the school district officials started to do a lot of switching in order to have African-American principals in white schools and white principals in African-American schools. The schools were supposed to be desegregated but they never were completely, even with a lot of bussing of students. So then the administrative desegregation was enacted which I thought was a good idea.

But, obviously, the Rebbe had been way ahead of anyone on this issue as well as many others – as he always was.

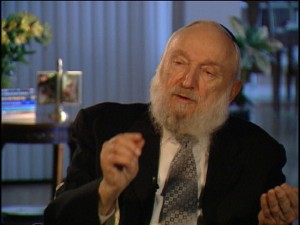

Mr. Frank (Efrayim) Moscowitz worked in the Chicago public school system for 38 years. He was interviewed in January, 2009.

This week’s Here’s My Story is dedicated

No Comments to “HMS: Knowing Chicago’s Ropes”